Learn Chinese For Kids Tip #1: Focus on Interest

by Woo Yen Yen

An English teacher’s journey towards getting her daughter to learn Chinese.

In this four-part series, former New York-based professor and “ang moh pai” (Western-Educated) English teacher Dr. Woo Yen Yen went from being that student who ripped up her Chinese textbook to writing Chinese comics and a giant musical that toured 25 cities in China. She shares her journey and how she got her American-born daughter with zero Chinese to thrive in an all-Chinese instruction Taiwanese public school.

This series of lectures was produced for the Singapore Ministry of Education’s Mother Tongues Languages Symposium 2020 and supported by the Speak Mandarin Campaign.

#speakmandarincampaign #bilingualism #chineseeducation #comics #multicultural #bilingualeducation

How do I spark my kids’ interest in learning Chinese?

Why is free time important to kids?In learning music or language, we often think that we have to plough through the basics, step by step, and move on to the next level only when we have mastered the basic level. It’s the reason why there are levelled readers in classrooms, why we have grading and exams in music, and different colored belts in Taekwondo.

Have you also noticed that many children practice and learn to play the piano for many years, say until grade 8 and then never play music again in their lives? Have you noticed that many of us who live in Singapore might study Chinese for many years but have never, ever read a novel in Chinese? My conjecture about why this happens is that these learners have never really felt ownership of the subject, and the process and curriculum never really ignited their interest. It’s something that “my parents want me to do” or something that “I have to study to pass the exam.”

While we always assume that we have to begin with the “BASICS”, I think that focus is wrong.

I think we have to begin with “INTEREST” and what is “INTERESTING”!

It’s not that the basics are not important, but that we should first engage interest. That will take us much much further. Because learning is for life, not just to pass exams.

John Dewey, the father of Progressive Education, tells us in Experience and Education (1938) that there must be experiential fireworks—those experiences which can arouse enough “curiosity”, that can strengthen “initiative” and align a learner’s “desires and purposes” enough, so that this spark can carry the learner through those hard parts of learning, when we have to work very, very hard in order to own the new knowledge. It means that effective learning begins with INTEREST!

What does it mean to begin with interest?

To Learn Chinese, Play With the Language

When YB was really young, I remember doing something pretty crazy. I would take her to the playground, and I found myself trying to direct her play. If she was at the monkey bars, after a while, I would get her to go to the swings. “Have you tried the swings? That looks pretty fun!” And then after she played with the swings, I would say “Ooh, look! The slides look really fun! Wanna try?” and so on.

I don’t really know why I did that. It might have been trying to make myself useful in the playground or it might have come out of the fear that my daughter would miss out on something.

I soon realized I was behaving crazily. I had to tell myself to stop directing her play and just leave her alone when she’s at the playground. When I left her alone, I found that she would run around with her friends, but often, she would return to the monkey bars and spend a lot of time at the monkey bars. She would repeatedly experiment with different movements at the monkey bars and begin to do things at the monkey bars that I had to look away from because otherwise I would stop her as it looked too dangerous!

I noticed that YB began to get really quite focused on the monkey bars as she started getting stronger and started being able to do new things at the monkey bars. Moving forwards, moving backwards, sideways, skipping rungs…

The other parents started noticing and I they would sometimes physically push their children to the monkey bars and go, “look, this little girl can do it, so can you” and get their kids to do what YB was doing. Gradually, some parents started to say to me, “You know, she’s strong, you should send her to swimming class or gymnastics” and “How did you train her to do this?”

But the truth is, I didn’t do anything except to let her have the time and freedom to play and “own” what she learned. And she was “good” simply because she spent many hours at the monkey bars and got stronger as a result. It looked easy not because she was a “natural” at it, it looked easy because she had spent hours and hours at the monkey bars playing on her own (look at

In fact, “playing” is very important in language learning as well. The work of “Translanguaging” experts like Professor Ofelia Garcia have shown that playing with the language we’re learning helps us feel like we own it, just as monkey bars became YB’s thing.

When YB comes home from school, we often talk about what she notices about “playing” with languages.

She is often tickled by the linguistic mash-ups of her classmates, e.g.:

为么”( “wèi mo”) is a contraction of “为什么”

The English letter ‘Q’ is used to describe the bouncy texture of food such as beef balls or meat.

Her Taiwanese friends use the English word “over” to mean “too much” or “extraneous”, as in “His acting in that movie 有点over.”

And she was very tickled when her classmates read 李白Li Bai’s famous poem like:

床前明月光,

疑是地上霜。

举头望明月,

低頭之便當. (instead of 低头思故乡)

And she really enjoys telling me jokes that she learned from school,

e.g. 为什么蜘蛛侠煮的面这么难吃?因为是 “失败的面“ (”Failure noodles” sounds like Spiderman)

These are not “correct” or pure, but they are fun and memorable linguistic experiences, and they are “play”. They have certainly made learning Chinese feel like play for YB.

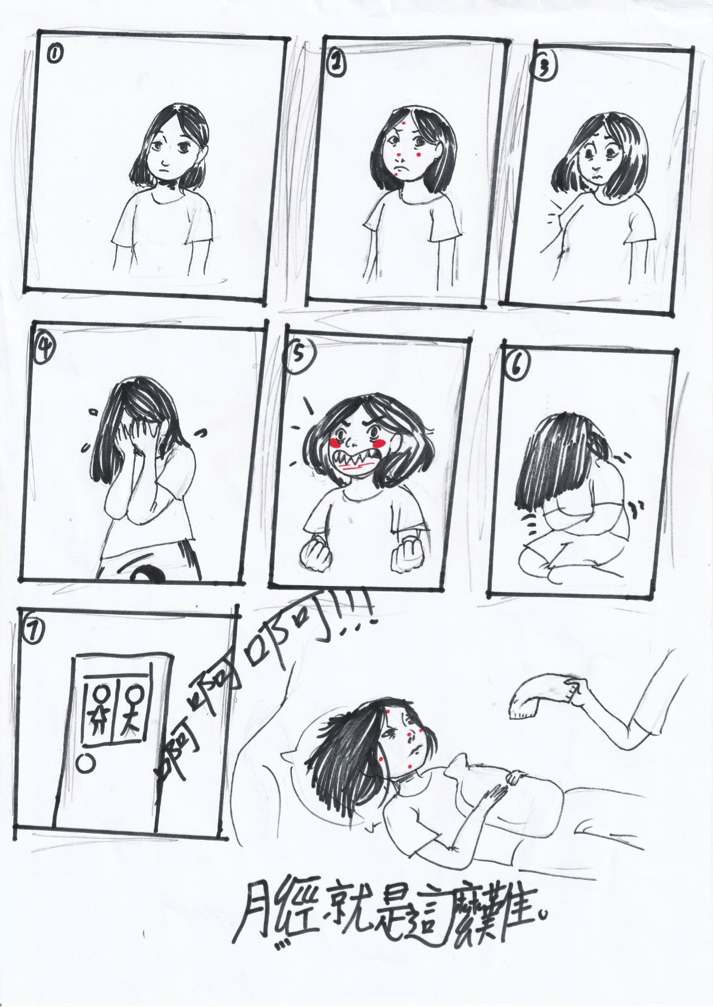

Her wonderful Chinese teacher this year at her Taipei public school has also noticed her interest in making comics and has actively encouraged her to express herself through her comics.

This comic that YB made sits at a prominent spot on the wall in her classroom. Even though her Chinese is still at a “basic” level, through playing, she is motivated to use it to express boldly, to provoke, and to make the language her own. Having a goal and a purpose of play and expressing in a form that will get a reaction makes her want to learn the basics. The goal could be as simple as learning to tell a silly joke in Chinese.

“Play with them”

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned about playing is that it’s not as fun to play on your own.

We adults can encourage our kids to go deeper by playing with them, or to facilitate by helping to find people and materials to play with. We don’t have to do much—we just have to pay attention and notice when our kids are welcoming that little bit of encouragement for them to go deeper.One way of “playing” with our kids is just to note what stories interest them.

So we recently engaged a Chinese tutor for YB for the summer holidays—not to prep her for tests or the coming school year, but mainly to help build her interest in Chinese. When YB mentioned to蕭老師 we’d been binge-watching the Chinese series, 《隐秘的角落》on iQiyi, 蕭老師went home and also watched the series, then brought the novel on which it was based so that she and YB could read it together. During the process, they discussed not just the text, but also the process of adaptation and why they felt certain creative decisions were made. This was not textbook curriculum, it was interest-based curriculum. And it really made Chinese come alive for YB in a way that just ordering her to memorize her textbooks would not.

Now, 《隐秘的角落》 is not necessarily something I’d recommend for kids. Although it’s about three elementary school kids, it’s actually a fairly dark crime thriller and social commentary, sort of like “Breaking Bad”. But the important point is, it was really encouraging for YB that when she mentioned something she’d been interested in, 蕭老師 paid attention and contributed to it and expanded the conversation.

We actively try to find opportunities for relaxed, unstructured, and low pressure play for YB with Chinese-speaking friends. She particularly likes playing dolls with one of her Taiwanese friends. Whenever they’re together, they would use Mandarin to create crazy scenarios with their dolls, often involving ridiculous dialogue. After the first time they’d played together, YB told me it was the first time she’d played in Chinese from the beginning to the end! That she continues to look forward to their playdates is really encouraging.

The key is that the play is unstructured and relaxed. Otherwise, it becomes work and it becomes yet another performance.

What can I contribute?

Professor Carol Tomlinson in her work on Differentiating Instruction talks about how every child, when they walk into the classroom or a learning community, will have an important question in her mind: “What can I contribute?”

And if the child cannot contribute because her knowledge is not valued or seen as not enough, the child either resists or withdraws instead of participating.

Think of the classes you have been most engaged in or from which you have learned the most. They are invariably the classes where your knowledge is valued or classes where you feel you have been able to contribute your knowledge. I remember being nervous in my own Chinese classes where I was always the one with the most number of “错字” and couldn’t contribute very much.

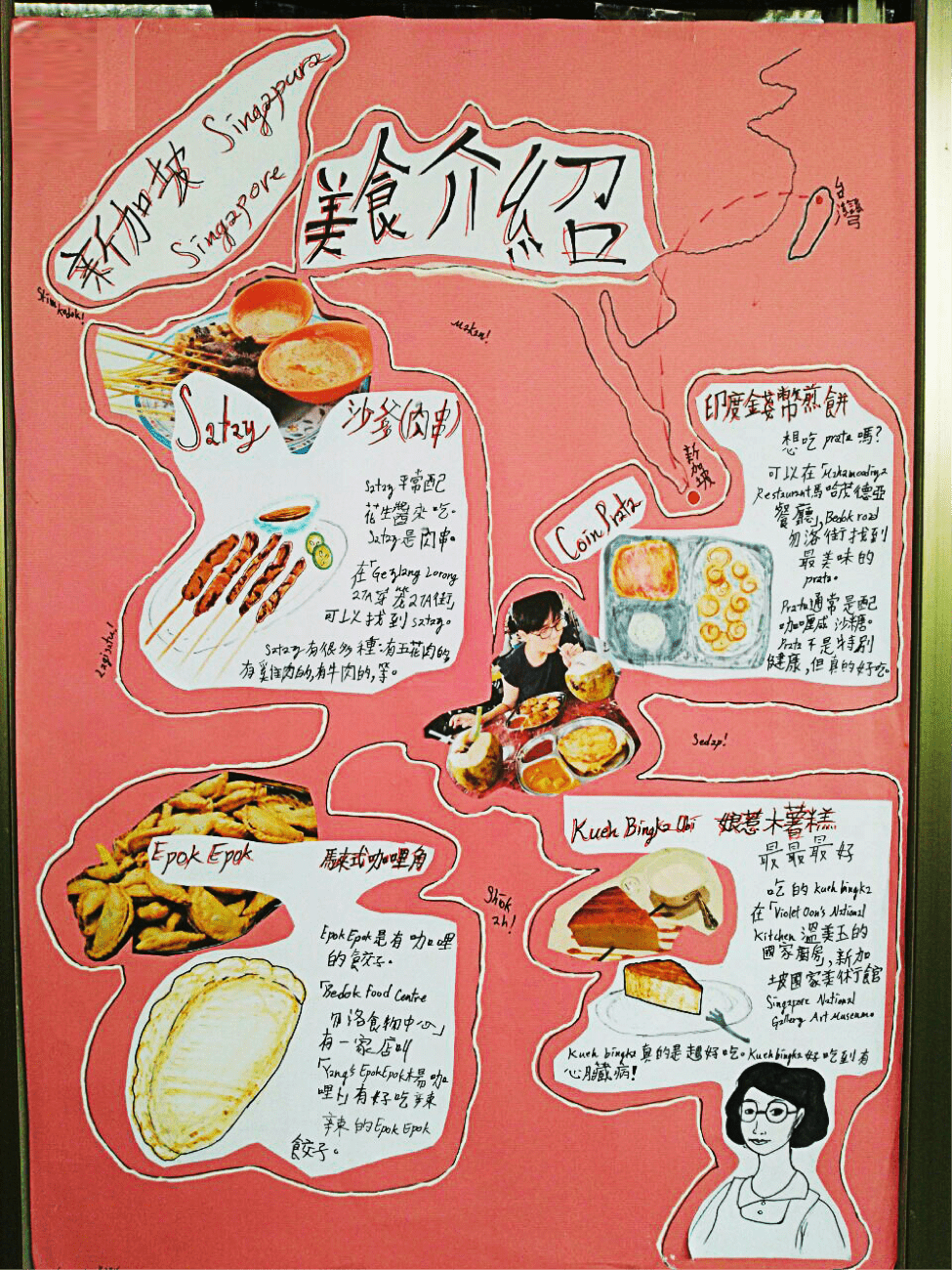

I have noticed that YB’s wonderful teacher, 李老師 , at her public elementary school works very hard to make sure that every child has an opportunity to contribute to the class. One assignment that got YB very engaged and which she worked very hard on was where the kids were asked to introduce food they loved to the class.

YB really threw herself into the project, did the research and produced this poster:

Yes, that is her rendition of a very young Violet Oon at the bottom right corner, because we often use Violet Oon’s cookbooks in our home. YB also had to get up in front of the class and talk about the poster in Chinese.

Yes, that is her rendition of a very young Violet Oon at the bottom right corner, because we often use Violet Oon’s cookbooks in our home. YB also had to get up in front of the class and talk about the poster in Chinese.

In another assignment, her teacher asked the class to research things that seniors in their own families created to make everyday living easier. So, for example, one kid shared that his grandma cut up rugs to use as toilet seat-warmers. YB shared that her Great Grandma used to freeze canned fruit in syrup in plastic tubes and sold these 冰棒.

The kids were very engaged in this research, writing and presentation exercise.

The kids were very engaged in this research, writing and presentation exercise.

This pedagogy is incredibly engaging as the kids weren’t simply filling in other people’s blanks, but using the language to research and tell their own stories. Professor Gloria-Ladson Billings calls this “culturally relevant pedagogy”, where the curriculum connects to students’ own stories and family cultures.

Protecting and valuing free time

When YB was in first grade back in New York, she had a teacher who was particularly focused on homework. She would assign book reports every day.

Even though YB could read far more difficult and longer texts, during that time, she was chose strategically to read only shorter books because that was the only way she could finish her book reports on time. So ironically, the homework made her read simpler, less complex texts, and made her merely busy rather than increasing her learning.

One day, she came home in tears. She told me that for days, she had been dreaming of an art project she’d come up with to dye dried leaves she’d collected. She thought she could do her project after school, but there was just so much homework, and after homework, there was dinner, and after dinner, it was bedtime. When would she ever have time to do her project?

My heart broke a little that day because YB was being told that her curiosity and creativity would have to take a backseat to mundane homework.

This is probably the most important point of all. What is the goal of learning anything—Chinese or any other subject?

Isn’t it so that our children can be smart and creative and innovative? Especially when we know that in our current and future world, most jobs are going to be replaced by AI and the only thing that will enable our kids to survive well in the age of Artificial Intelligence is Human Intelligence, a major component of which must be creativity!

Professor John Dewey talks about how we are all so concerned with preparing our kids for the future that we actually miss the “real preparation.” In his book, “Creating Innovators”, Tony Wagner researched several of the most interesting innovators and creators in the US and he found that one common theme throughout the interviews was how these innovators attributed their ability to create to having the free time to tinker and play. That is how they came to realize what they’re interested in, and what completely engaged them.

Homework was displacing Yakuza Baby’s time for play, experimentation, and processing and organizing her thoughts. I thought: if I don’t give her time to create and experiment independently now, how do I expect her to create and experiment independently in the future?

So that day, I told her not to worry about her homework and to just go ahead with her project. It’s a real challenge to protect YB’s free time, even to the extent of telling her teacher that she is only allowed an hour or homework per day. She sets a timer and starts and ends her homework in an hour. She ends up doing it all pretty quickly.

Can we protect our children’s free time—the time to create and experiment—so they can make what they are learning their own? While we are worried about whether our children can learn enough Chinese or maths or whatever, we actually have a much more important worry: that all the classes, the tuition, the time and stress would be for nothing if our children don’t know how to create, experiment, and grow the part of them that makes them uniquely them.

Summary:

We often hear “go with the kids’ interests”, but just don’t know how to. I have demonstrated a few ways:

1. Playing with the language

2. Finding ways that our kids can contribute their own knowledge

3. And most important, we need to protect and value free time, because that’s actually extremely productive time.

Continue to Part 4: “How do we become confident with our languages?”

Dr. Yen Yen Woo works on educating for a multicultural and multilingual world through popular culture. She most recently co-created the Dim Sum Warriors app, characters and stories for Bilingual Learning. She has a Doctorate in Education from Teachers College, Columbia University and has been a tenured professor of education. She is also an award-winning film director and screenwriter. Her works have been licensed by HBO and Netflix and featured on BBC, Fast Company, Wired, and other global publications. Email: yenyen@dimsumwarriors.com.