Happy Mid-Autumn Festival! 中秋节快乐!

(Zhōngqiū jié kuàilè)

The Mid-Autumn Festival 中秋节 (Zhōngqiū jié) is one of the most important festivals in Chinese culture. It’s called “Mid-Autumn” because it is celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month in the Chinese calendar, which is usually around the autumn harvest period, and is always accompanied by a full moon. It’s been celebrated for over 3000 years!

As you’d expect from a festival built around the full moon, many of the legends growing out of 中秋节 have to do with the moon.

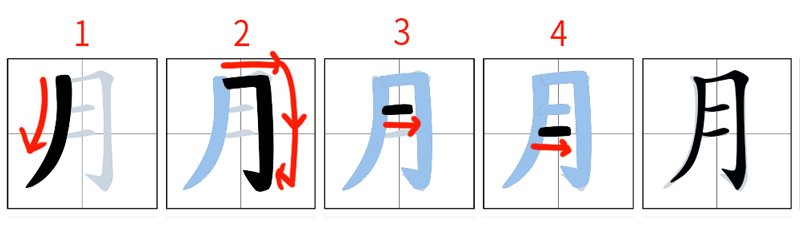

Why do we write the Moon as 月?

It probably has to do with how the ancient Chinese tried to depict the crescent moon, and it evolved from there.

Let’s write ‘Moon’ in Chinese: 月

RESIDENTS OF THE MOON

Chang’e 嫦娥 the Moon Goddess

Probably the most famous of all the Chinese moon legends, 嫦娥 Cháng’é (pronounced “Chang Er“) is worshipped by some during the Mid-Autumn Festival as the Goddess of the Moon.

In fact, the lunar probes sent by the People’s Republic of China’s space programme are all named after Chang’e.

The Chinese Moon Goddess Chang’e (嫦娥) from a painting done sometime during the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644). It is now displayed in the

Chang’e was married to Houyi 后羿 Hòu Yì, a famous archer. (I guess you could say he was the Hawkeye or Green Arrow of ancient China.)

Houyi got famous because one day, ten suns appeared in the sky, and as you’d expect, things got uncomfortably hot. So Houyi shot nine of them down—with his bow and arrows! (Wish he could be around to teach us how to deal with climate change in such a cheap way.)

Thankfully, he left us one sun.

The Gods rewarded Houyi by giving him either a pill or elixir of immortality—whoever ate it would become a god and live forever.

Here’s where the legends diverge.

Version 1:

Houyi had a jealous apprentice named 逢蒙 (either Féng Méng or Péng Méng), who tried to steal the pill of immortality for himself.

But Chang’e managed to grab the pill first, and swallowed it so that Peng Meng couldn’t get it.

She thus became an immortal and ascended to the moon.

Version 2:

Peng Meng was not involved.

Rather, after his heroic act, Houyi became an evil king.

To save the world from an evil king who could now live forever, Chang’e ate the pill herself, and then became an immortal who flew up to the moon.

In both Versions 1 and 2, Houyi missed her so much that he started making offerings of food to her, and that’s why many people make offerings to Chang’e up till today.

BUT:

Version 3:

Houyi wasn’t evil; Chang’e was greedy.

She stole the pill from him while he was sleeping, ate it and flew up to the moon.

Houyi got angry and tried to shoot her down as she flew up, but failed. (Maybe his heart wasn’t in it, or maybe it’s harder to hit a person than a whole sun.)

Eventually, he got over his anger and started missing her, so he started making offerings to her.

So in all 3 versions, Chang’e takes the pill of immortality, flies up to the moon, and that’s why we make offerings to her as the Moon Goddess.

But here’s where the tales take an even weirder turn.

Chang’e 嫦娥 the Moon Toad 蟾蜍

(chánchú)

There are 2 variants of the greedy Chang’e version—both of which involve her becoming a toad! 蟾蜍 (chánchú).

Note: in Chinese, a toad can either be called 蟾蜍 chánchú or 癞哈蟆 lài hā má. But when it comes to Chang’e, it’s always chánchú.

Variant 1:

The Gods decided to punish Chang’e by turning her into a toad 蟾蜍 (chánchú).

Variant 2:

Chang’e changes herself into a toad to make it harder for Houyi to fire arrows at her.

Here’s an etching from the Han Dynasty of Chang’e flying to the moon to become a toad.

Bummer, right? Not necessarily.

Toads aren’t necessarily unlucky in Chinese culture.

In fact, there are separate legends about a magical lucky toad appearing around the full moon. (I guess that’s the Chang’e connection.)

These toads are often referred to as 金蟾 jīn chán (Golden Toads) or 招财蟾蜍 zhāocái chánchú (wealth-welcoming toads).

You’ve probably seen them in Chinese shops. They’re usually in the form of a small statuette of a toad with 3 legs (only 1 hind leg), sitting on a heap of coins, with a coin in its mouth.

One of the earliest mentions of the Moon Toad is in the 楚辞 (Chǔ cí, ‘The Words of Chu’), a book of poetry written during the Warring States period (roughly 221 BCE) mostly by 屈原 Qūyuán—yes, that Quyuan, the dude in whose memory we have Dragon Boat races and rice dumplings during 端午节 Duānwǔ jié.

The other moon animal that’s mentioned in the Chuci is this next little fella.

The Jade Rabbit 玉兔

(Yùtù)

After Chang’e, the next most famous Chinese lunar resident is 玉兔 Yùtù the Jade Rabbit.

The Jade Rabbit is Chang’e’s companion on the moon, where it pounds herbs to make the elixir/pills of immortality for the gods, as well as Chang’e. (I guess they need the occasional top up?)

But how did this bunny get to the moon?

The earliest version of this story comes from the ancient Buddhist Jataka Tales.

In the story, several animals (the Indian version has a monkey, a jackal, an otter and the rabbit, while Chinese versions have just a monkey, a fox and a rabbit) meet an old man begging for food.

The monkey gets him fruit from the trees.

The otter/fox gets him fish from the river.

The jackal brings a lizard he stole from somewhere.

The rabbit knows only how to gather grass—so it offers itself to the old man, by jumping straight into the old man’s fire!

But the rabbit didn’t die. Because the old man was actually the ruler of Heaven——in Buddhist lore: Śakra, Lord of the Celestials; in Taoist legend: the Jade Emperor 玉皇大帝 (Yùhuáng Dàdì).

In the Buddhist version, Śakra deems the rabbit the most selfless of creatures, and draws its image on the moon for everyone to see.

In the Chinese version, the Jade Emperor rewards the rabbit by teaching it how to make the elixir of immortality, making it the pharmacist to the gods.

Then he stations the rabbit on the moon so that pesky humans can’t get the elixirs so easily.

Actually, not just India and China, but many other cultures also have legends about an immortal rabbit on the moon—including Japan, Korea, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and even the Mayans and Aztecs.

No doubt because if you look at the full moon with a bit of imagination, you can sort-of see the shape of a rabbit, and maybe also its pestle and mortar…

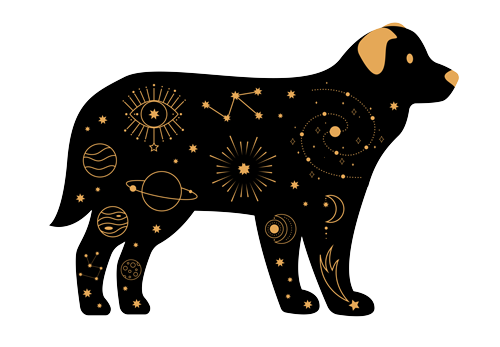

Tiangou 天狗 the Heavenly Dog

(Tiāngǒu)

Remember the version of the Chang’e story where she’s greedy?

Well, instead of her turning into a toad, there’s a version where her husband Houyi also happens to have a pet dog.

When Chang’e flies to the moon, the dog manages to lick some leftover bits of the pill/elixir of immortality, and begins to chase Chang’e.

As the elixir kicks in, the dog could also now fly and was growing bigger and bigger.

Chang’e reaches the moon, but the dog was now so huge, it swallows the entire moon and Chang’e too.

The disappearance of the moon startles the Queen Mother of the West (西王母 Xīwángmǔ or 王母娘娘 Wángmǔniángniáng), who is the Taoist goddess of longevity, immortality and life—and also the Jade Emperor’s wife.

She comes to investigate, and finds out that the dog is Houyi’s.

She makes it spit the moon and Chang’e back out, then renames the dog 天狗 Tiāngǒu (meaning ‘Heavenly or Sky Dog’), and gives it the job of guarding the Southern Gate of Heaven.

According to legend, Tiangou actually has two forms: one is a white-headed fox who brings protection, and the other is a black dog who swallows the sun or moon, causing eclipses.

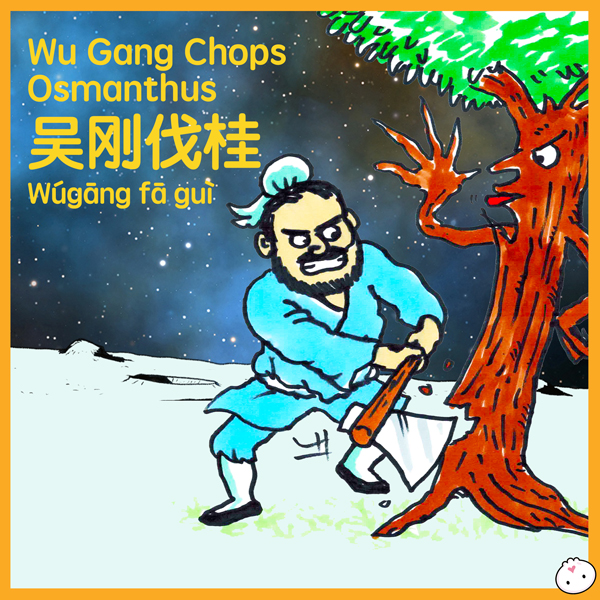

吴刚 Wu Gang, the Eternal Woodcutter

吴刚 Wú Gāng is the only other human on the moon, and he’s stuck there as a form of punishment.

There are several versions of the legend, but the most popular one has him wanting to become an immortal— but he gets lazy and goofs off after only a short while.

As punishment, the Jade Emperor tells him he can become an immortal by simply going to the moon and chopping down an Osmanthus tree.

But it’s a trick! Wu Gang finds that the tree instantly heals after every chop, and he now has to chop it for all eternity.

Well, I guess he did become an immortal after all—pity about the catch. (That’ll teach him to goof off!)

It’s very traditional to drink Osmanthus tea 桂花茶 guìhuāchá and wine 桂花酒 Guìhuā jiǔ during the Mid-Autumn Festival, and if you do drink any, spare a thought for poor old Wu Gang chopping away up there…

灯笼 LANTERNS!

Lanterns are a big part of the Mid-Autumn celebrations.

In Guangdong and Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore, colorful lanterns in all shapes and sizes are displayed or paraded around by children.

Check out this wonderful video by Walking Singapore of the Mid-Autumn lantern display in Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay:

In mainland China, hanging up lanterns for the Mid-Autumn Festival is called 竖中秋 (shù zhōng qiū) or “Hoisting Mid-Autumn”. The higher the lanterns are hoisted, the more luck will come your way! Here are some of the mid-autumn lightups across China:

The Mid-Autumn Festival is not Taiwan’s primary lantern festival—that is during the Chinese New Year. However, in Pingxi, sky lanterns with wishes written on their sides are launched into the air—a spectacular and chyarming event!

Weirdly, in Taiwan, the primary Mid-Autumn Festival tradition has become holding barbecues! This only began in the mid to late 1980s, when two major Taiwanese soy sauce manufacturers, Wan Ja Shan Food and Kimlan Food, engaged in an advertising war to sell their barbecue sauces.

月饼 MOONCAKES!

Eating mooncakes 月饼 (yuèbǐng) and pomelos 柚子 (yòuzi) while sipping tea as you admire the full moon 赏月 (shǎng yuè) are the most traditional things you can do during the Mid-Autumn Festival.

The most famous mooncakes are the traditional Cantonese ones, filled with lotus seed paste 莲蓉 (lián róng) and salted egg yolks 咸蛋 (xián dàn).

But now there are so many different flavors, pastry textures, fillings and designs, not to mention the increasingly elaborate packaging to justify the ever-increasing price tags!

The most famous legend surrounding mooncakes is about how they were used to overthrow the Yuan Dynasty (set up by the Mongols) and establish the Ming Dynasty.

There were apparently 2 methods:

(1) Concealed messages baked inside the mooncakes;

(2) Secret messages carved onto the pastry, which when assembled a particular way, revealed the instructions.

ACTIVITY TIME!

Let’s Draw Some Mooncakes!

Let’s try drawing a traditional Cantonese-style mooncake.

Let’s draw another version… with some of its filling (white lotus paste 莲蓉 and a salted egg yolk 咸蛋) peeking out!

OK, now that you’ve got the basics, let’s get silly and draw some silly mooncakes!

What happens when you mix food 食物 shíwù … with superheroes 超级英雄 chāojí yīngxióng?

Since it’s the Mid-Autumn Festival, what happens when you mashup a Mooncake月饼 (yuèbǐng) with the amazing Spider-Man 蜘蛛人 zhīzhū rén? You get… Spider-Mooncake! 蜘蛛月饼人 zhīzhū yuèbǐng rén!

Like Japanese anime? Well, there’s no better super-heroine for the Mid-Autumn Festival 中秋节 (zhōngqiū jié) than this mashup of a Mooncake月饼 (yuèbǐng) with the legendary Sailor Moon 水手月亮 (shuǐshǒu yuèliàng): SAILOR MOONCAKE 水手月饼 shuǐshǒu yuèbǐng!

Did you know? In the original Japanese manga and anime, Sailor Moon’s secret identity is Tsukino Usagi (月野 うさぎ) which can be translated as the Moon Rabbit!

JOIN OUR DOODLE DATES!

If you enjoyed these, you’ll love our Doodle Dates! Throw crazy combo suggestions at our cartoonist Colin to draw, while picking up some Chinese vocabulary from our certified Chinese teachers!

We hope you had fun learning about 中秋节 with us!